Edit sorry about the odd formatting. When I copy and posted it removed most of the return. And I’m on mobile. Will try to fix later.

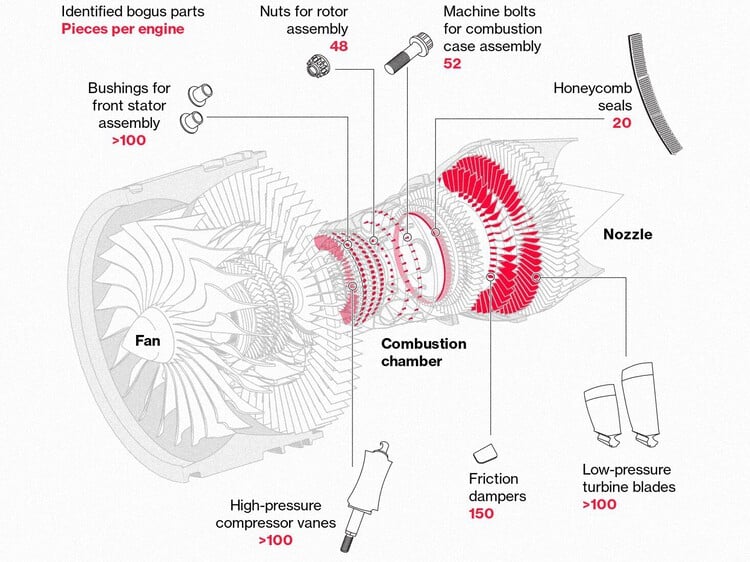

A little-known distributor in London sold thousands of engine components with bogus documentation. Carriers and repair shops are frantically hunting them down. This spring, engineers at TAP Air Portugal’s maintenance subsidiary huddled around an aircraft engine that had come in for repair. The exposed CFM56 turbine looked like just another routine job for a shop that handles more than 100 engines a year. Only this time, there was cause for alarm. Workers noticed that a replacement part, a damper to reduce vibration, showed signs of wear, when the accompanying paperwork identified the component as fresh from the production line. On June 21, TAP pointed out the discrepancy to Safran SA, the French aerospace company that makes CFM engines together with General Electric Co. Safran quickly determined that the paperwork had been forged. The signature wasn’t that of a company employee, and the reference and purchase order numbers on the part also didn’t add up. To date, Safran and GE have uncovered more than 90 other certificates that had similarly been falsified. Bogus parts have been found on 126 engines, and all are linked to the same parts distributor in London: AOG Technics Ltd., a little-known outfit started eight years ago by a young entrepreneur named Jose Alejandro Zamora Yrala. While engineers are trained to spot components of dubious origin, “it’s always shocking when we have one in front of our eyes,” said a person familiar with the revelation, who asked not to be identified discussing internal deliberations. The discovery by an alert crew in Lisbon blew the cover off a massive aviation fraud that has left engine makers and their customers in a frantic race to stem the fallout. As a result of the fabrications, thousands of parts with improper documentation have wound up at airlines, distributors and workshops around the globe. From there, they’ve ended up inside jet engines, effectively contaminating a growing portion of the world’s most widely flown airliner fleet. This story is based on legal and corporate filings, regulatory disclosures and social-media accounts, as well as information obtained from industry executives and people familiar with Zamora’s career, who asked not to be identified given the sensitive nature of the relationships.

All major US carriers and half a dozen others have identified bogus parts from AOG on their airplanes. While no flight emergencies have been called due to engine malfunctions, the audacity of the scam, dating back several years, highlights a risky gap in a system that’s made flying the world’s safest form of transportation. And the ease at which safety protocols were breached has prompted soul-searching in an industry where a decades-old system has suddenly revealed worrying loopholes. “If people want to cheat, it’s going to be hard to stop them,” said Tim Zemanovic, who runs Fillmore Aviation LLC, a Minneapolis-area company that sells recycled aircraft parts. “There’s a lot of trust involved.” Read more: Fake Spare Parts Were Supplied to Fix Top-Selling Jet Engine Hardly a week has passed by since late August, when Bloomberg first reported on the scandal, without another airline finding so-called suspected unapproved parts on older-generation Airbus SE A320 or Boeing Co. 737 aircraft. Complicating the search is the fact that the CFM56 is by far the most widely flown engine, with more than 22,000 units still in service — a CFM56-powered aircraft takes off every two seconds somewhere on the planet. Given the global nature of aviation, parts with fabricated certificates have now washed up everywhere, from the US to China to as far away as Australia. Behind the furor is an upstart distributor with the veneer of respectability. On its now-deleted website, AOG boasted of warehouses in the UK, Singapore, Frankfurt and Miami, calling itself a “leading global aircraft support provider’’ with a mission to “keep our clients flying.” Its inventory of parts was listed on the biggest online clearinghouse. A quality-assurance organization endorsed by the Federal Aviation Administration had accredited AOG’s practices.

Historically, regulators have kept a watchful eye over airlines and the planes they put into the sky. Individual parts that get swapped in and out when a jet comes in for repairs have their own carefully documented history. Bundles of paperwork tell a story of inspections, overhauls and whether a part can still be safely used. Such relentless obsession with safety and record-keeping can’t mask the fact that within the industry lies an essentially self-regulated, highly lucrative marketplace: parts distribution. Here, intermediaries help circulate hundreds of thousands of parts each year between manufacturers, airlines and repair stations. Personal connections mean sourcing specialists buy and sell from vendors they know. Into this clubby world stepped a young, part-time DJ originally from Venezuela. In 2015, Zamora established AOG in Hove, corporate records show. From the sleepy coastal town about an hour’s train ride south of London, Zamora spent the next few years expanding his network. He eventually relocated to an upmarket London office address — in reality, just a mail drop rented from a co-working provider. Zamora hasn’t engaged in attempts to get his side of the story. Reached briefly by phone on Oct. 5, he hung up when he was told he was speaking with a reporter. Zamora’s wife, Sarah Leddin, said that Bloomberg had been “trying to paint him out to be some bad person or something.” “He doesn’t want to talk to anyone because the information is fabricated at best,” she said by phone. Zamora’s barrister, Tom Cleaver with the legal firm Blackstone Chambers, hasn’t responded to attempts seeking comment.

Long-term acquaintances say they’ve not heard from Zamora in months. He told Doug Hensley, the chief safety and regulatory counsel at GE Aerospace, on Aug. 2 that he was out of the country on vacation. He had, however, in the meantime stopped selling GE and CFM-related parts “as a courtesy,’’ legal filings show. GE and Safran are now facing off with AOG in a London court. The CFM International engine-making partners had sought a court order for the documents relating to “every single sale of products.” AOG produced the records on Oct. 4, giving CFM fresh potential leads. The European Union Aviation Safety Agency said it has no power to investigate AOG because suppliers are not regulated. The FAA said it encourages companies to maintain a system to detect unapproved parts and to review their suppliers. Maintenance companies and airlines that repair planes have the responsibility to ensure any component installed on an aircraft is an approved, legitimate part, and the FAA lacks the resources to do so, a spokesperson said. The UK Civil Aviation Authority said it supports the FAA and EASA as they look into the supply of unapproved parts by AOG. Born in 1988, Zamora dabbled in professions from music to real estate before settling into the world of aircraft parts. For a while, he spun techno tunes under the stage name Santa Militia in Venezuela, Italy and Spain. In 2022, he married Leddin, an interior designer, on the island of Mallorca. The couple was photographed at the rural luxury retreat, sporting matching Rolex watches and cradling a pair of babies dressed in identical cream-colored rompers. Zamora began his aerospace career around 2010 as an account manager at AJW, a prominent engine maintenance provider better known as Walters in aviation circles. There, he dealt with airlines based in Latin America — from AeroMexico and Avianca to Brazil’s GOL. He later moved on to the UK operation of Florida-based maintenance company GA Telesis LLC, before eventually setting up AOG. He typically worked from home, logging onto the ILS platform, an aerospace-parts marketplace, to check out requests from airlines and maintenance shops and which components were available, according to a person familiar with his routine. AOG started off humbly. After a year in business, the brokerage had just £7,804 in cash, company filings show. The fledgling company moved from residence to residence around the London area over the next few years as its sales gradually grew. By early 2019, it had £18,295 in cash and made a profit of £22,042, the records show. Then business abruptly prospered. For the year ending February 2020, AOG reported £2.43 million in cash and a profit of £2.2 million, company records show. That’s shortly after AOG began selling thousands of jet-engine parts with falsified documents, the engine makers allege, in what Matthew Reeve, a lawyer for CFM, has described in legal filings as a sophisticated deception “on an industrial scale.” Legal filings reveal the scope and means of the alleged fraud. Forgeries turned up at an engine services provider northeast of London, a parts supplier in Florida, a maintenance firm in Scandinavia, an airline in Africa and another maintenance outfit incorporated in Germany, among others. Forged records cited by CFM’s lawyers were dated as far back as 2018, suggesting a years-long deception. Some bore faked signatures of actual Safran employees, while others were signed off by former workers. Then there’s a certain Geoffrey Chirac, who shares a last name with the late French president. CFM says in legal filings his signature was forged. Other signatories appear to have also been fabricated: several forms were signed by a Michael Smith. His now-deleted LinkedIn profile presented him as a purported AOG quality assurance manager. But his profile picture can also be found on stock-image sites, where he’s described as a “confident senior man in white T-shirt.” The photo is particularly popular in the medical profession, featuring on the websites of a Wisconsin cardiologist, an Oregon dentist and a Barcelona rectal surgeon.

LinkedIn profiles of some purported AOG executives also used stock photos that appeared on other websites. Companies listed on the profiles as former employers say they have no records of these people. Read more: Bogus Supplier of Jet-Engine Parts May Have Fake Workers Too How an intensely regulated and safety-obsessed industry could be deceived by a single rogue outfit remains one of the big mysteries of the unfolding case. It’s a vulnerability the aviation industry has been dealing with for decades, but has never successfully addressed. The most high-profile accident involving fake parts occurred on Sept. 8, 1989, when Partnair Flight 394 carrying 55 people from Oslo to Hamburg crashed into the sea, killing everyone on board. Investigators later determined that counterfeit bolts and brackets had caused the tail section of the Convair CV-580 turboprop to vibrate violently and eventually tear loose.

A rash of bogus aircraft parts sparked a furor in the 1990s. As the US Transportation Department’s Inspector General at the time, Mary Schiavo led investigations into fake parts that helped secure about 120 criminal convictions between 1990 and 1996. She told a Senate oversight panel in 1995 that the industry was so awash with suspect components that one “must unavoidably draw this conclusion: if it is a part of an airplane, it could be bogus.” She also sparred with FAA officials, whom she accused of downplaying the potential risks posed by unapproved parts. In Schiavo’s view, AOG’s alleged misdeeds show that vulnerability continues to exist today. “We were busting people and sending them to prison 20 years ago for this,” she said in an interview. “It’s the same old scheme.” The FAA released a voluntary program in 1996 for parts sellers to agree to audits and other checks by industry organizations in order to accredit their quality practices. The idea was to address a lack of documentation and traceability plaguing distributors at the time, without further straining the FAA’s already limited resources. Almost three decades later, bogus parts continue to pose possible safety risks. And as if to illustrate the point, CFM made another, more troubling discovery: having reviewed nearly 600 of its material suppliers, it, too had been directly duped by AOG. The engine maker’s own shops installed parts sold by AOG in 16 CFM56 engines. In four instances, parts from the rogue firm made their way into CFM’s network, including one lot purchased directly from the UK company. Subsequently, CFM inspectors noticed some major discrepancies with the parts in question, which AOG had represented as brand-new. For example, the low-pressure turbine blades CFM bought weren’t as bright as they should have been. They also showed signs of welding and residual corrosion, something that shouldn’t have appeared on new parts. CFM concluded that the parts were in fact repaired, used components. The company says it plans to review its practices for evaluating suppliers. “What you need to do is know that your supply chain, the providers you’re dealing with, are reputable,” said Willie Walsh, director general of the International Air Transport Association. “It’s like anything: know who your partner is, know their track record, that they know who their partners are and that the chain is secure.” While quality departments are meant to keep an eye out for suspicious activity — and the threat of jail to discourage faked parts and forged documents — there are real-world limitations. In practice, documentation relies on paper records, and there is no centralized repository, meaning much of the verification is performed on the basis of faith in the records. The financial and operational cost of having to remove parts stands to be considerable. Charges could quickly rise to about $300,000 per engine, depending on how deep teams need to furrow, said Adil Slimani, the director of aftermarket advisory at consultant IBA Group. Then there’s the lost revenue from idling an aircraft that is an industry workhorse. “Hopefully you have a routine to go through all your thousands of records one by one to see if AOG was in them — and to look three suppliers deep,” said Roy Resto, a consultant who specializes in aircraft maintenance. Airlines that have discovered suspect parts have been advised by regulators to remove them. In the case of AOG, these have turned out not to be harmless components like armrests or coffee machines, but instead bearings and turbine blades crucial to a modern jet engine. In a worst case, they could be discarded or damaged components that have no business being in the unforgiving heart of a jet engine. There, temperatures run hotter than the melting point of metal and blades can spin at more than 10,000 revolutions per minute. For now at least, AOG’s alleged misdeeds don’t appear to present an immediate risk to flight safety. There’s no evidence that so-called life-limited parts — the most safety-critical components in an engine that by law must be removed after a certain number of flights — were involved. Examples in court filings point to used components masquerading as new, rather than wholesale knock-offs. Still, the AOG scandal renews questions about what critics say has been a weak link in aviation safety for decades. In 2021, AOG’s operations were accredited by Transonic Aviation Consultants Inc., one of only a handful of organizations deemed acceptable by the FAA to confer that designation. By then, AOG’s alleged scheme was already well under way. Transonic CEO Bob Pina said a subcontractor hired by his firm inspected AOG’s operation in London and reported back that everything appeared to be in order. Pina said he stripped the company of its accreditation in early September, immediately after learning of the alleged forgeries. Like others in the industry, Pina said he was “bamboozled” by Zamora, saying there was little he could do head off his alleged misdeeds. “You can’t do any type of inspection to find out if people are bad,” Pina said. “They appeared to be good, but once you turn your back on them, rats will do what rats will do.” One of the world’s largest parts distributors is pushing to bring more oversight to their business. GA Telesis CEO Abdol Moabery has urged lawmakers in Washington to convene a hearing about unapproved parts in aviation, in the hope that Congress will push the FAA to impose some form of regulation on companies like his. But tracing parts and providing seamless documentation is time-consuming and costly.

“I have 17 inspectors that do nothing but look at paperwork,” Moabery said. “That’s expensive.” The temptation to cut corners won’t go away any time soon. A post-Covid shortage of both parts and labor has dramatically crimped aircraft availability, putting additional pressure on airlines and maintenance shops — and creating a fertile ground for opportunists. This squeeze is especially acute for older engines that power a previous generation of narrowbody Airbus and Boeing workhorses. While airlines are slowly moving to newer models, their predecessors are still among the most popular aircraft in the skies today. “Wherever there’s money, there’s fraud,” said Zemanovic, the Minneapolis parts recycler.

“I felt exactly how you would feel if you were getting ready to launch and knew you were sitting on top of two million parts — all built by the lowest bidder on a government contract.”

John Glenn